Letter for Letter

|

A life-long passion for printing led to the creation of one of Melbourne's

least known, most hands-on museums, writes Viviane Stappmanns.

|

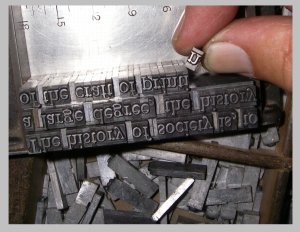

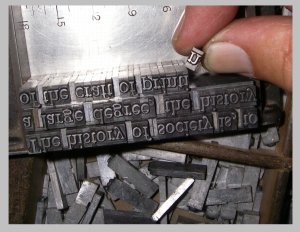

''The history of society is, to a large degree, the history of the craft of

printing.'' Laurie Harding may be retired, but the speed at which he picks up the

leaden letters to compose this sentence tells a story of his decades of experience.

Ironically, Harding himself is living proof of what he's spelling out; the huge

changes in the printing industry during the latter half of the 20th century meant that

the trained hand-compositor was made redundant after 28 years working for a commercial

printer. His services, like those of the machines that surround him here at the

Melbourne Museum of Printing, were no longer required.

Ironically, Harding himself is living proof of what he's spelling out; the huge

changes in the printing industry during the latter half of the 20th century meant that

the trained hand-compositor was made redundant after 28 years working for a commercial

printer. His services, like those of the machines that surround him here at the

Melbourne Museum of Printing, were no longer required.

''I loved my job, but (the development of) technology went faster than I was, and I

suppose there were people who were cleverer than I was,'' says Harding.

His former industry has now largely forgotten about the old ways. The tedious

typesetting process, where every line of type had to be composed in matrices, cast by

a machine in lead, assembled into pages, printed and later melted to be used again was

slowly replaced by the cleaner, quieter, faster and more colourful printing methods of

today. These new methods produce with lightning speed what people like Harding used to

do by hand. But Harding's new workplace, the Melbourne Museum of Printing, is a place

where the environment, working techniques and aesthetics of a printing process that

remained largely unchanged for centuries (since Germany's Johannes Gutenberg

first invented moveable type in 1450) can live on. As a volunteer at the museum, a

little-known, drafty warehouse across the road from Footscray's art precinct, where

the advertisement for another tenant , ''Crazy T-shirts'', almost obliterates its

modest signage, Harding assumes his position at reception every Sunday and Thursday,

the museum's days of operation.

Acting as cashier, guide and education officer, the 61-year-old collects the small entry fee

from the few visitors who arrive at this counter, makes them read the occupational health

and safety notice and points toward the ''hand washing facilities'' (this is a rare hands-on

museum).

Then it's off to a wild ride through hundreds of years of printing, illustrated by the

still-active printing presses and typecasting machines that stand crowded between shelves of

wood type blocks.

Who would have known that the expressions ''upper case'' and ''lower case'', which we so

casually use today, are actually derived from the fact that capital letters used to be

picked from a typecase that was mounted above the one that stored the other letter-forms?

As Harding talks, he encourages newcomers to experiment with wooden type that is arranged in

boxes in the crammed shelves. There are no cordons and no ''don't touch signs''.

And while they serve as artefacts, almost all machines on display are in working order.

They're used by a small group of students of graphic arts and design from the city's

universities who find their way here either with their lecturers or on their own initiative.

The printed sheets dispayed on the walls or suspended with pegs at the back of the room give

evidence that the occasional local or international celebrity from the type design world has

seen the inside of this space, which can be rented out by graphic design studios interested

in experimenting with the old way of doing things, an aesthetic that is increasingly gaining

popularity.

One of the regular drop-ins is Nick Doslov, one of Melbourne's few master bookbinders

who hasn't succumbed to the machine-made binding techniques of today, but still works by

hand in his Fitzroy-based business, Renaissance Bookbinding. Doslov comes in on weekends to

work on art projects with the staff and to exchange tips on creating wood cut type with the

museum's founder Michael Isaachsen, Harding and other volunteers.

Another is Joyce Zhang, a 22-year-old graphic design student from China. Since she

found the museum on the Internet, she has been coming in on Sundays. ''She can now set type

and knows the basic processes,'' says Harding, ''we're helping her with the rest.''

It is the second incarnation of the museum, which originally opened in 1990 but closed eight

years later due to lease expiry. In 2005, Isaachsen, who can passionately explain the

history of each and every artefact in his museum, once again wrested the doors open to the

public.

''I've been a printing enthusiast since I was nine, and had a printing press in my bedroom

since I was 11,'' says Isaachsen, now in his mid-60s. Although he devoted most of his

professional career to another form of communication as an engineer for a telephone company,

Isaachsen always found himself returning to his beloved types and presses.

Passion finally became profession in the late 1970s, when Isaachsen realised that the advent

of computer aided printing meant that the older printing presses and typesetting material

would hit the scrap heap.

''I just couldn't see all those things being thrown away, I thought that one day these would

be valuable assets. I wanted to preserve some of them.'' He set up shop as the Australian

Type Company, selling old-fashioned movable type founts to fellow enthusiasts and the few

companies who still operated with the traditional technology. ''As everyone else was closing

down, I opened up, I was Australia's newest typefounder'' says Isaachsen. Yet as he kept

buying the type from companies that upgraded, he ended up buying their printing machines

too, as well as tens of thousands of other artefacts, including ''saved typesettings'' for

the stationery of hundreds of Australian companies. ''I thought some day researchers will be

interested in studying this,'' he said. And so, slowly but surely, Isaachsen's collection

increased to fill up more and more warehouse space.

Today, what's on display at the modest museum is only the tip of an iceberg that includes

more than 200 printing printing and typesetting machines and other printing paraphernalia,

housed in five or so other locations, but not accessible to the public - yet. Together, they

tell - in the spirit of that sentence that Harding continues to spell out for visitors - a

story not only of printing but of Victorian society. One of the smaller hand-operated

presses sports a haphazard pencilled tag, stating that it was collected from the Heidelberg

Repatriation Hospital, were veterans performed basic printing jobs as they recovered.

Isaachsen hopes that the school classes who used to visit the museum prior to its closure in

1998 will return. ''Schoolteachers of art, design or history used to come with their entire

class, but not many know that we're open again,'' he says, admitting that marketing

isn't exactly one of his strongest sides, although he proudly points out that when he

published the museum website in 1996, he was one of the first to advertise in this way.

Isaachsen hopes that the school classes who used to visit the museum prior to its closure in

1998 will return. ''Schoolteachers of art, design or history used to come with their entire

class, but not many know that we're open again,'' he says, admitting that marketing

isn't exactly one of his strongest sides, although he proudly points out that when he

published the museum website in 1996, he was one of the first to advertise in this way.

One day, hopes Isaachsen, there will be a fully-fledged printing museum, displaying all

kinds of presses and typesetters, and hopefully replicating the noise and bustle of the

composing and printing rooms that Isaachsen learned to love as a child. He's considered all

eventualities, producing an elaborate floor plan for what could be. ''I am sure some day

someone will show interest in researching, cataloguing and exhibiting this huge

collection,'' says Isaachsen, ''even if I might not be around to see it.''

|

Ironically, Harding himself is living proof of what he's spelling out; the huge

changes in the printing industry during the latter half of the 20th century meant that

the trained hand-compositor was made redundant after 28 years working for a commercial

printer. His services, like those of the machines that surround him here at the

Melbourne Museum of Printing, were no longer required.

Ironically, Harding himself is living proof of what he's spelling out; the huge

changes in the printing industry during the latter half of the 20th century meant that

the trained hand-compositor was made redundant after 28 years working for a commercial

printer. His services, like those of the machines that surround him here at the

Melbourne Museum of Printing, were no longer required. Isaachsen hopes that the school classes who used to visit the museum prior to its closure in

1998 will return. ''Schoolteachers of art, design or history used to come with their entire

class, but not many know that we're open again,'' he says, admitting that marketing

isn't exactly one of his strongest sides, although he proudly points out that when he

published the museum website in 1996, he was one of the first to advertise in this way.

Isaachsen hopes that the school classes who used to visit the museum prior to its closure in

1998 will return. ''Schoolteachers of art, design or history used to come with their entire

class, but not many know that we're open again,'' he says, admitting that marketing

isn't exactly one of his strongest sides, although he proudly points out that when he

published the museum website in 1996, he was one of the first to advertise in this way.